The day had barely dawned, but the phone’s alarm wailed, transforming a summer Saturday morning into a workday. The temperature had already climbed to the upper 80s, and a hazy and humid film blanketed the city. Most people were clinging to their beds and air-conditioning. Most people didn’t dare to step foot outside and brave the heat.

Most people weren’t Amseshem Foluké.

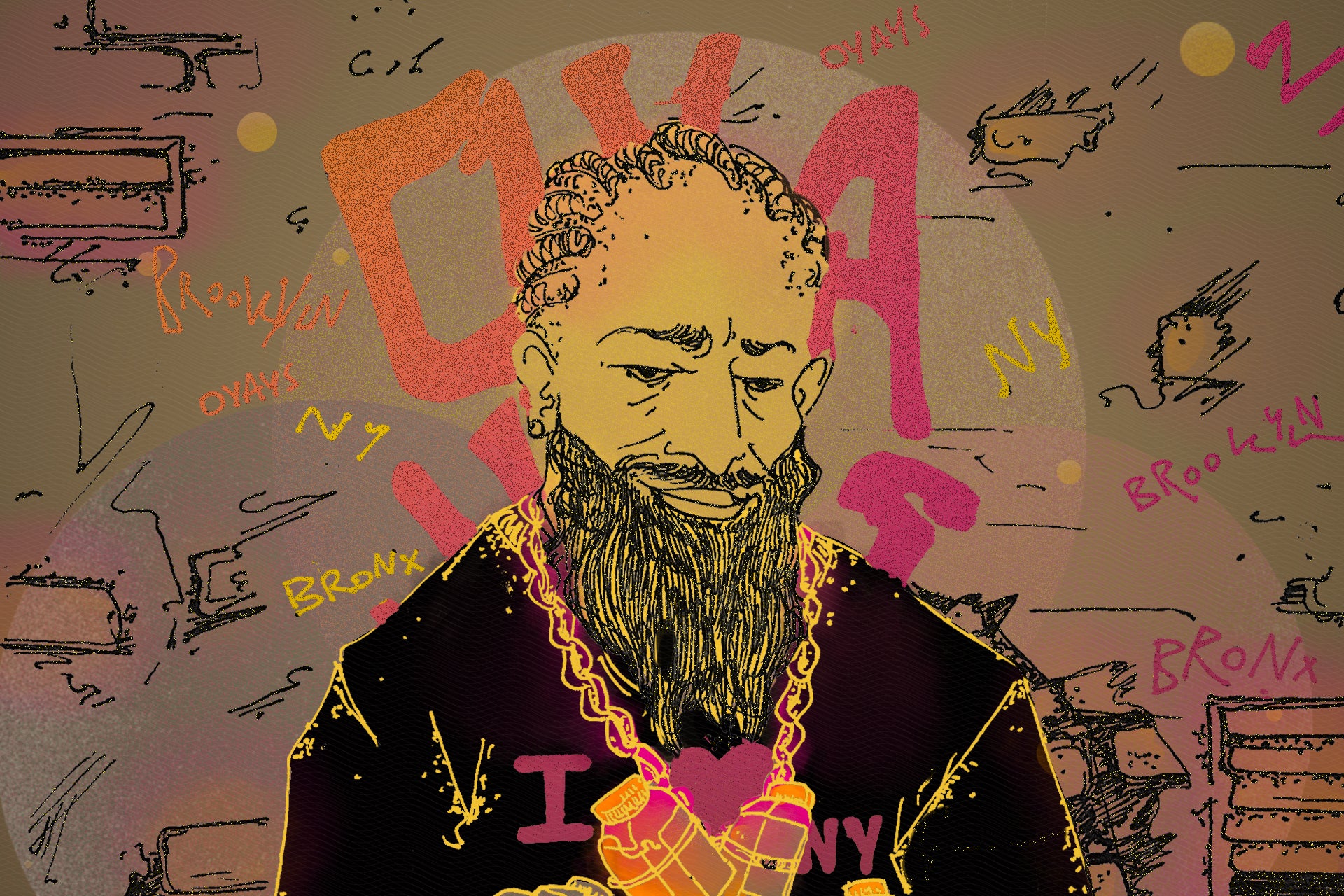

Equal parts hustler and savvy businessman, the New York native began most days knowing that it could be his last one in operation. His homemade product, an alcoholic drink called Oyays, was wildly popular, and his social media promotion videos often went viral, but the law wasn’t on his side and Foluké became a hunted man. Selling liquor without a license — like all independent street sellers are forced to do — is illegal since only those with physical bricks-and-mortar locations qualify for licensing. Like his Prohibition predecessors, this modern-day bootlegger was ruffling the feathers of the powers that be, and they threatened to put his solo operation out of business and crush the dream he had nurtured for almost two decades.

Bootlegging from the Bronx to Brooklyn

Sometime in the early 1990s — no one seems to remember exactly when — a bar known as Flor de Mayo in the Washington Heights area of New York City began selling a drink called Nut Cracker after the manager and an ironically-named customer called 'Juice' haphazardly invented it by mixing liquor remnants from the bar’s nearly empty shelves and a motley array of fruit juices. The TV mounted above the bar happened to be broadcasting an ad for The Nutcracker ballet and, as many culinary origin stories go, a legend was born out of sheer serendipity. They added the cocktail to the menu as a joke, but after customers began demanding more flavours, quickly realised they had a serious success on their hands.

Soon after, industrious entrepreneurs began selling their own simple concoctions of sugary fruit juice, hard liquor, and a host of varying ingredients (at times, including hard candy). In its earliest iteration, the summertime hit was known as jungle juice on the street market, but the name eventually morphed into its current moniker and now nutcracker serves as a sort of umbrella term for the boozy drinks. Makers of the potent, candy-coloured beverages guarded their recipes fiercely and, with no two sellers’ measurements and ingredients being identical, New York streets were rife with competition for customers and cash.

In 2005, Foluké, a video producer and former pro basketball player, saw an opportunity to get in on the street drink game and started experimenting and mixing nutcrackers in his college dorm room and eventually his home kitchen. He touted coolers filled with his rum punch and mango Patrón cocktails all over New York City and could easily make $500 in a half-hour weekend stint on any given corner (he reports making about $20,000 a month pre-pandemic).

Determined to defy stereotypes, he avoided the drug trade that dominated New York streets at the time and made slinging drinks his hustle. In fact, the name Oyay is ‘yayo’ spelled backwards (yayo being urban slang for cocaine). He chose the backward spelling as a metaphor — a literal shuffling of letters to show that he had flipped the game and challenged the prevailing notion that all street hustlers were drug dealers.