According to Janet, the discovery was made in 1817 when gardeners were replanting rhubarb roots that had been buried under land drains installed that winter. To their surprise, they noticed delicate pink sticks sprouting from the plants and recognised the potential significance. “Thank goodness it was Chelsea where the horticulturists were, so they didn’t just put their foot on those sticks but were intrigued,” she says.

The discovery of such a nutritional crop that could grow in the cold was a gift in the early 19th century, at a time when there was no refrigeration and seasonal fruit and vegetables were stored through winter. The longer these crops were stored, the more nutrients they lost. Here, they had a product that was growing in winter and was packed full of nutrients – eureka!

The Science Behind Forced Rhubarb

How can it be possible for a plant to grow without light? In the case of Yorkshire forced rhubarb, the root must sit outside on the Rhubarb Triangle’s moist soil for at least two years after propagation. Left to its own devices rather than harvested, the root hoards energy as it photosynthesises, preparing the rhubarb for a rapid yet brief working life inside the sheds. Just one season in the forcing shed and this fragile plant is as good as dead.

Cloaked in the intense gloom of the forcing sheds, in the depths of winter, frosts kick-start a chemical reaction that awakens the plant and forces it to produce a crop.

At Janet’s farm, E Oldroyd & Sons, the crops are tended to by candlelight with painstaking regularity. Her farm-hands measure the frost units every morning, then, when they’re just right, they warm the sheds using what is essentially central heating, and gently moisten the plants by misting them.

The entire growing operation is a lengthy, delicate balancing act: not enough frost and the rhubarb butt won’t produce sticks; too much moisture and the root will rot. Allow any light to enter the sheds and photosynthesis will occur, which causes the rhubarb fibres to thicken and makes the product tougher. Photosynthesis also increases the levels of oxalic acid in rhubarb; the more photosynthesis, the sharper rhubarb tastes. Force the rhubarb too quickly and it loses flavour – farmers in the Rhubarb Triangle take a first harvest only after six to nine weeks.

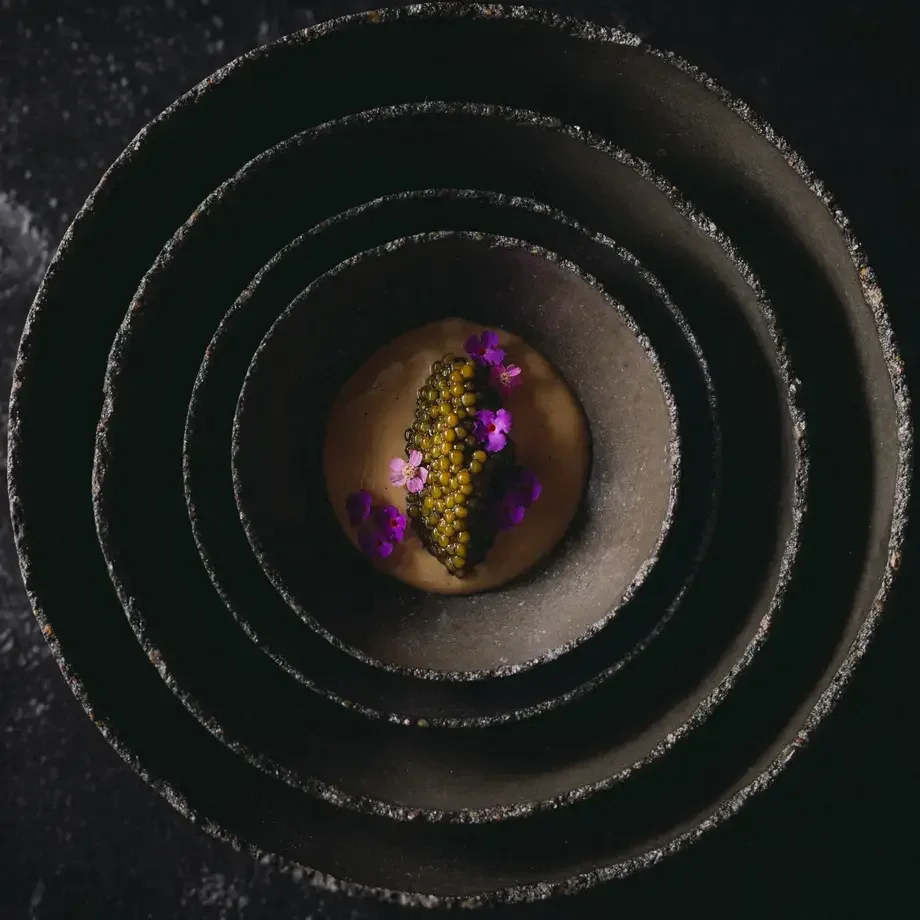

Supplying the Stars of Britain’s Restaurant Scene

Janet’s farms supply the three-Michelin-starred restaurants The Fat Duck in Bray and Hélène Darroze at The Connaught in London. Other Michelin-starred restaurants that put forced rhubarb on the menu in winter include Tommy Banks’ The Black Swan at Oldstead in North Yorkshire, while visitors to the farm have included the likes of chefs Raymond Blanc and Rick Stein.

“Chefs are always interested in the forced,” says Janet, who is in the process of erecting more sheds to keep up with increasing demand. But now chefs are experimenting with savoury recipes as well as sweet, eschewing the traditional custard and sugar, and using forced rhubarb to sear through fatty meats and fish like duck and mackerel.

“And it’s about time,” says Janet, “because this plant is so versatile in cooking – thank goodness the chefs are showing how to get more rhubarb into your body and what lovely recipes you can come up with.”