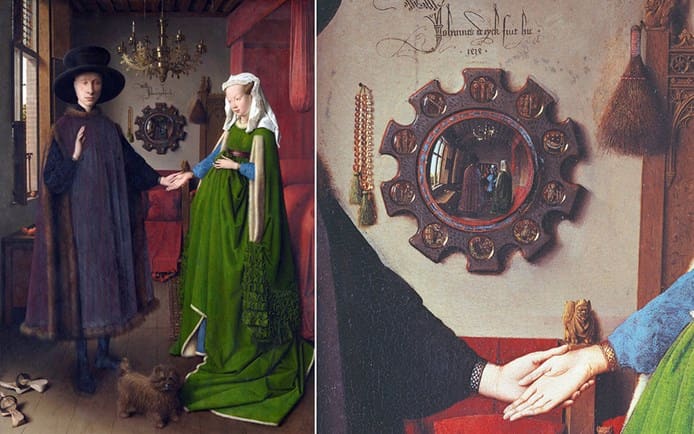

Marriage ceremonies at the time required only the presence of two witnesses and the couple holding hands and reciting a vow. The couple are barefoot, suggesting that a holy ceremony is taking place. If you squint you can see two people reflected in the convex mirror at the back, one with a blue turban, one with a red – the artist, Jan van Eyck, liked to paint himself wearing a red turban, so that’s him. He also signed the work prominently, right in the middle, centuries before artists normally signed their work – suggesting that this painting functions as a contract, signed by one of the witnesses.

There’s a dog, symbolising the loyalty of the couple to one another, and those are oranges on the window ledge. Does this mean that the Arnolfini family really loved citrus, and without a fridge, preferred to leave it around their bedroom? No, you guessed it – the oranges are representative of the prosperity and wealth of the family. An orange is a symbol of prosperity in Northern Renaissance paintings. This isn’t valid in Spanish art. Why? Because oranges grow in Spain and were commonplace there, of no particular status to buy and consume, whereas in Flanders they were extremely expensive, having to be laboriously imported from Spain, and therefore only consumed by the wealthy.